Introduction

We use our physical bodies in our everyday life to maneuver, navigate, and communicate (Hansen & Morrison 2014). Many interactive systems, analogue or digital, involve the role of bodily movement as an embodied interaction. Dourish P once argued that the role of embodied interaction hinges on the relationship between action and meaning (Dourish 2001), which is extremely crucial for any form of design. Human cognition can be “performed” using moving bodies as an embodied nature. Therefore, we can argue that physical embodied interaction in the study of interaction design is often movement-based. All humans actions including cognition are embodied actions (Loke et al. 2007), that’s what makes it essential to the recent trend of movement design in interaction design.According to Loke & Anderson’s 2010 Study of Dancers, because “interactive technologies is movement-based”, it’s “continuing to become more embedded in our daily lives” and “our interactions with these technologies are becoming sought-after qualities” (Loke & Anderson, 2010, pp. 39).

Drawing from pre-existing research on movement design as well as my personal experience with movement design in practice, this paper acts as an argumentative essay that proposes how movement can be articulated for the purposes of design, .

Defining Interaction

A major part of Interaction Design circulates around designing human interaction with digital products in addition to the study of how people interact with analogue products. When we look at the word interaction by and of itself, we can argue that it is associated to a situation or context where two or more objects or people communicate with each other or somehow “react” to one another (Cambridge Dictionary Online, 2008. Interaction, n.d.). Objects and objects can interact, human to human can also interact. But in the essence of interaction design, we focus on the interaction between people and objects.

Let’s consider the word “react”. A “reaction” is a behaviour that can arguably be a form of interaction, that being said, reacting or “behaving” a certain way can be perceived as a movement in addition to a simple spark of thought in the head. What’s targeted here is an embodied movement. Researchers in Interaction design look at experiences felt and performed by users they’re designing for (Interaction Design Glossary), and a big part of experience involves the interaction between the user and a certain product. Targeting the moment of usage, some sort of movement is most certainly involved— some examples include the act of pulling down a projection screen involves the extension of the arm to reach the string and the tugging and contraction of the elbow to lock the screen in place, the act of entering an unmonitored 24/7 gym involves swiping your card then standing still for motion detectors to sense your presence and confirm that you’re not cheating the system by bringing in an extra person, etcetera. This can all be studied as a performance if we see the way we display ourselves as an act (Goffman 1959 & Hansen & Morrison 2014). We adjust our posture, our body language, and the scope of which we move our limbs to handle our weight and balance according to the context we’re involved in and what we are hoping to express (Hansen & Morrison 2014).

The Technology of Identifying and Defining Movement

Movement-based interaction in design with technology is an emerging area that demands an improved focus on the human body and its capacity for movement (Loke et al. 2005). An abundance of researchers in design have contributed their perspectives on the relationships between embodied actions and technology design (Loke et al. 2007). People interact and move with, sometimes unwittingly, an increasing amount of technology— either with ones that involve directness and focus such as a computer or omnipresent technology that you inadvertently move through with such as the WiFi. This technology often influences how we move, or “react”. To study performance and movement, researchers have discovered and spawned many ways to explore this similar terrain and emerging field (Loke & Anderson 2010). For example, Loke et al. also used an established movement notation called Labanotation as a design tool for movement-based interaction using the human body as a direct input, this time using two different EyetoyTM interactive games (Loke et al., 2005). Loke and Anderson also utilized trained dancers’ moving bodies this time as an input into sensor technology to find ways of analyzing movement and discover useful consummations for the field of movement-based design and or interaction design (Loke & Anderson 2010).

It is evident that movement design has been a crucial part of research in interaction design, and all the preexisting research done using some sort of a movement-based input that influences an output provides an invaluable groundwork for design of movement-based interaction. Loke & Anderson argues that this form of research can suggest “possible ways of describing, representing and experiencing movement for use in the design of video-based, motion-sensing technologies” (Loke & Anderson, 2010, pp. 39).

Tracking and influencing of movement is becoming exponentially important as movement design is being investigated in a grander scale as part of interaction design. Designers today have access to movement data through sensors like our iPhone’s accelerometers and gyroscopes, or other gadgets such as the Kinenct. The truth however is that very few resources exist in interaction design to “meaningfully engage with full-body movement data (Hansen & Morrison 2014) compared to the resources provided for other studies in interaction design, as movement is often times abstracted and nuanced, and arguably also inconsistent. That is why the tracking and influencing of movement reveals its importance in this specific study.

As students in the field of interaction design, we were granted the opportunity to dig further in the idea of finding ways to better articulate movement for the benefits of design by examining our everyday practice of movement. When discussing movement, we’re neglecting subtle movements such as swiping screens and pressing buttons, but performing an exploration of the entire body, hopefully finding potential for innovation of movement that can contribute to the exploration and creation of novel embodied interactions.

Movement design in Practice

For Module III of the interactivity course, students were given the opportunity to explore machine learning code using movement as an input. Having worked with pre-trained models for visual recognition in Module II, this round involves the utilization of machine learning models and movement data registered from movement sensors in our smartphones with the goal of gathering knowledge of what machine learning is as well as to gather knowledge of the practicality and usability of machine learning as a material in design and exploring its usefulness in movement design or in the general scope of IxD, as well as in the broader context of AI. Ultimately, the aim is to explore new gestures for movement that can potentially take charge in the field of Interaction design.

Getting inspired by Loke & Robertson (2010)’s notation for describing movement

Though the project involves the handling of machine learning models and technology, the overall aim was to design interactive systems from explorations of movement as opposed to targeting the technologies and using it as a starting point (Loke & Anderson 2010).

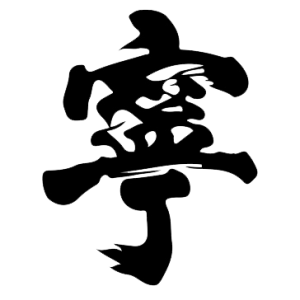

When we selected our specific gesture— the “YES!” gesture, which involves a swiping motion of an extended arm completed by the curling motion formed by the contraction of the elbow (see Figure 1), which was first taken out as an interesting gesture drawn from the action of pitching a baseball— we participated in first-hand exploration of the movement, we digitally recorded our gesture as performed in different contexts for transcription purposes, and later performed an in-depth analysis on our gesture inspired by Loke & Anderson’s notation for describing experiential qualities to fully grasp our selected movement (Loke & Anderson 2010).

Using videos as a way of referencing, as well as cropping frame by frame from our videos to have static images to reference to and to ease the process of jotting notes— we examined the process of pitching and in a later iteration: the “YES!” gesture. We performed analysis on our videos and static images using two unique perspectives—an experiential perspective, produced by first-person impressions of the gesture, think felt experience and bodily awareness, and an external, observational perspective that produced visual movement sequences (see Figure 2.). In other words, the mover and the observer perspective (Loke & Anderson 2010). This form of analysis granted us in generating a list of descriptions of the twisting body that we didn’t think we’d be able to come up with prior to this session of analysis. For example, “Hiding” and “Shielding” are descriptions we discovered to be synonymous with the “YES!” swipe, which was interesting because the “YES!” gesture is used to express extreme content and has obviously positive connotations. We believe this wouldn’t have been explored if we did not sit down and discuss the “felt” or “experiential” quality in detail after performing the action ourselves.

Challenges in movement— Vitality

The vitality, or livelines and spirit, in our interaction with technology is a sought-after quality (Loke & Anderson 2010). However, it serves as one of the main challenges for movement design technologically. The computer has trouble sensing exuberance, or almost any other emotion, as all it sees are specific data points and coordinates that it has been pre-trained to recognize. As humans to other humans, we naturally experience people in terms of vitality as we can often predict and calculate their emotions based on the subtle nuances and authenticity in their body language. However, that’s something the computer lacks to classify as movements are never “consistent”, “there is nothing rock solid in movement” (Hansen & Morrison 2014), people perform certain movements differently, with different expressions, dynamics, and nuances.

We noticed this issue during our process as the machine learning code was rather inconsistent and erratic when it came to predicting the right gestures. Though both my partner and I were doing the gesture in what we think is the same way, the computer would predict the right gesture only when I performed it, since I was the one that recorded the gestures initially. In the first module even, was it obvious that machine learning may not be the most accurate in processing movement data. That being said, what became more crucial in this module three project was how we described the experiential quality of our movement, which proves to us that ultimately machines may not be the best at articulating movement, while linguistics can do a significantly better job.

Conclusion—

How Movement can be Articulated for the purpose of Design

Interaction design, as described as movement-based (Loke & Anderson 2010, Loke et al. 2007, Loke et al. 2005), raises new questions regarding the consequences and the influences the moving body can provide in HCI. I argue that movement plays an essential role in design because movement is often incorporated as an aspect of behaviour, and behaviour is closely investigated in part of user-experience design, because paying attention to this role of embodiment often articulates this association between action and meaning (Dourish 2001).

In design, and perhaps even in fields involving computing, movement is often and arguably best articulated through data. Data is important and relevant because it allows for informed decisions. It allows computer models to better understand movements and elect or fit an appropropriate responses. Data for movement is unique as it delineates both arithmetics as well as bodily awareness qualities. In design, data is vastly used to alleviate the stress in putting effort and required preciseness demanded on humans. Thanks to computer vision, artificial intelligence, and the fast-growing smart technologies, human-errors are greatly reduced. Computers do a great job at seeing what we can’t and is also quick at processing an abundance of importance within a blink in time. They take up these tasks that some humans can’t, or mitigates the task for us.

Throughout this module however, we have learned that data isn’t necessarily the only way of articulating movement. And there are definitely prevalent cons utilizing only data to articulate movement— seeing how our machine learning predictions have undergone many miscalculations in predictions due to the model’s inability to recognize subtle nuances. Yes, the computer may be good at categorizing many data points and predicting the meaning behind that certain gestures, or “what gesture” it is, but it cannot possibly (at least not currently), accurately predict what meaning is insinuated behind each gesture. That can only be “felt” and “experienced” by the person doing it first-hand, even the observer can make mistakes in assuming based on individual bias. What I’m saying here is that when we see a person doing the “YES!” swipe, we don’t know if this person is expressing joy because they won a lottery, or because their holding their arm close to their core to hide something from being visible to others. If the observer has a hard time doing that, the machine definitely cannot be 100% accurate in predicting that too.

Addressing the articulation of movement, I guess the most ideal form of articulating movement would be a combination of all three perspectives like Loke & Anderson has advocated for (Loke & Anderson 2010). All three perspectives, the mover (the felt quality, first person experiencing), the observer (the outside observing the visual movement and its sequences), and the machine (the computer, machine learning models, artificial intelligence, etc). Simply articulating a gesture or movement based on one perspective may result in inaccuracies. The computer cannot recognize the most subtle nuances and sense vitality, but the human may miss specific nuances as well by not being able to see the movement as a whole and quickly calculate a big picture or system in their head.

Word-count:

2,299

References:

Dourish, P. (2001) Where the Action Is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Hansen, L. A., & Morrison, A. (2014). Materializing Movement-Designing for Movement-based Digital Interaction. International Journal of Design 8(1), Retrieved from http://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/1245/614.

Loke, L., Larssen, A. T., & Robertson, T. (2005). Labanotation for design of movement-based interaction. In Proc. of the 2nd Australasian Conf. on Interactive Entertainment, pp. 113-120.

Loke, Lian & Larssen, Astrid & Robertson, Toni & Edwards, Jenny. (2007). Understanding movement for interaction design: Frameworks and approaches. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. 11. pp. 691-701. 10.1007/s00779-006-0132-1.

Loke, L., & Robertson, T. (2010). Studies of dancers: Moving from experience to interaction design. International Journal of Design 4(2), pp. 39-54.

Background Referencing:

Interaction Design Glossary at http://www.interaction- design.org

Cambridge University Press. (2008). Cambridge online dictionary, Cambridge Dictionary online.